TL;DR — This is the intro to a three-piece article series discussing key decisions in designing developer experience and development cycle for teams in a microservices architecture.

A few years back, the tech world raced into the shiny new concept of microservices — and ran into a ton of new challenges. I do not believe anyone has foreseen the magnitude of the amount of tooling, methodologies, and knowledge needed to support what we have today. This battle is still far from over. I’d say we continuously learn and evolve as an industry. 👷 🙌

The spotlight of this battle shines brightly on some specific sets of issues relating mainly to production management at scale and infrastructure tools. Some other areas, focusing on development cycle, tend to rightfully receive less attention. These areas can sometimes create complexity, confusion, and frustration for development teams.😵 On the other hand, they can provide powerful assurances and increase production reliability. In a microservices architecture, development cycle tools are a powerful thing, we’re going to discuss what they are and how to correctly tune them to achieve a well-designed developer experience. 💻 🤔

Designing developer experience, either when refactoring an existing product or designing a new one, includes three strategic decisions: Version control layout, code sharing, and testing strategies. These decisions will affect many factors in the developer experience and development cycle of the teams involved. Some examples of such factors are source code management, testing strategies, releasing strategies, deployment strategies, tooling complexity, environment flexibility, and the ramp-up times of new team members.

Like any other engineering space, there’s no right or wrong. Each decision has pros and cons to consider. I intend to use this series of articles to shed some light on the design decisions to be made, the approaches available for each decision, and the pros and cons of each approach. 📊 📈

Each article in this series will focus on a specific design decision:

- Version control layout

- Code sharing

- Testing strategies

I’m writing this series with a desire to gain clarity and guide myself towards better decision-making. I’ve decided to share it to get feedback and improve. Please help improve it by correcting and sharing back your knowledge. You can comment on each article, share feedback on social media or write to me directly. ✏️ 🙏

During this series, we will rely heavily on production architecture as it plays a key factor in our decision-making. Namely, a specific aspect of production architecture.

Consistent Version Guarantee

In order to better argue for the value of each decision during this series, we’ll define consistent version guarantee between components A and B as:

Each version of component A is guaranteed to interact exclusively with a certain version of component B.

In a consistent version environment, we can design a much simpler developer experience, saving money and countless hours of frustration. On the other hand, it may introduce drawbacks in production. However, we’re not here to guide production decisions, we’re simply here to observe production architecture as it is, and design the best development environment to support it. 💪😎

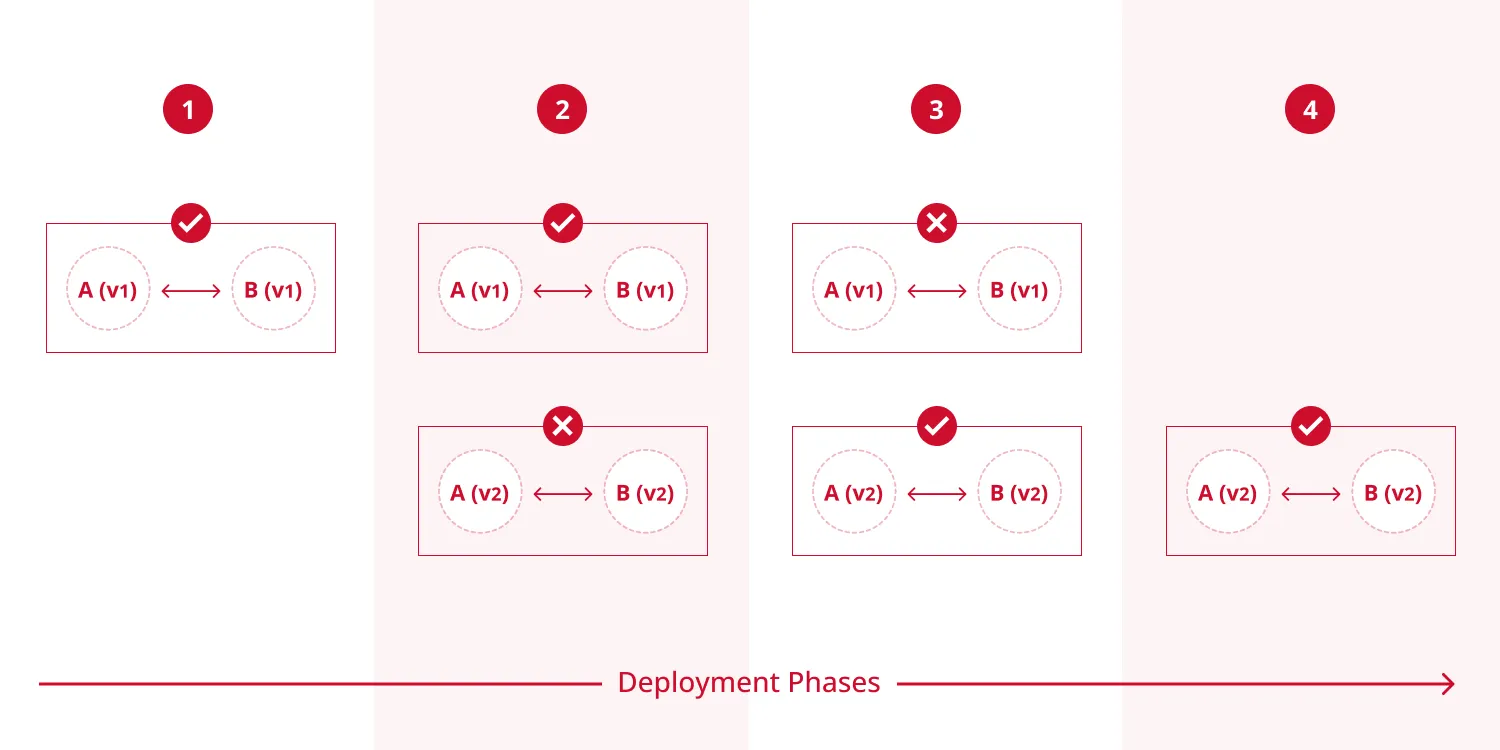

So, what do consistent version environments look like? And inconsistent version environments? Let’s provide several examples for clarity.

Example I: Consistent Version Environment via Deployment Architecture

In this example, we have two different applications — A and B — deployed on the same machine and interacting solely with each other. When we want to update either of them, we replace the entire machine with a new one. This environment guarantees that component A on a certain machine will only interact with the deployed version of component B on that machine and vice versa.

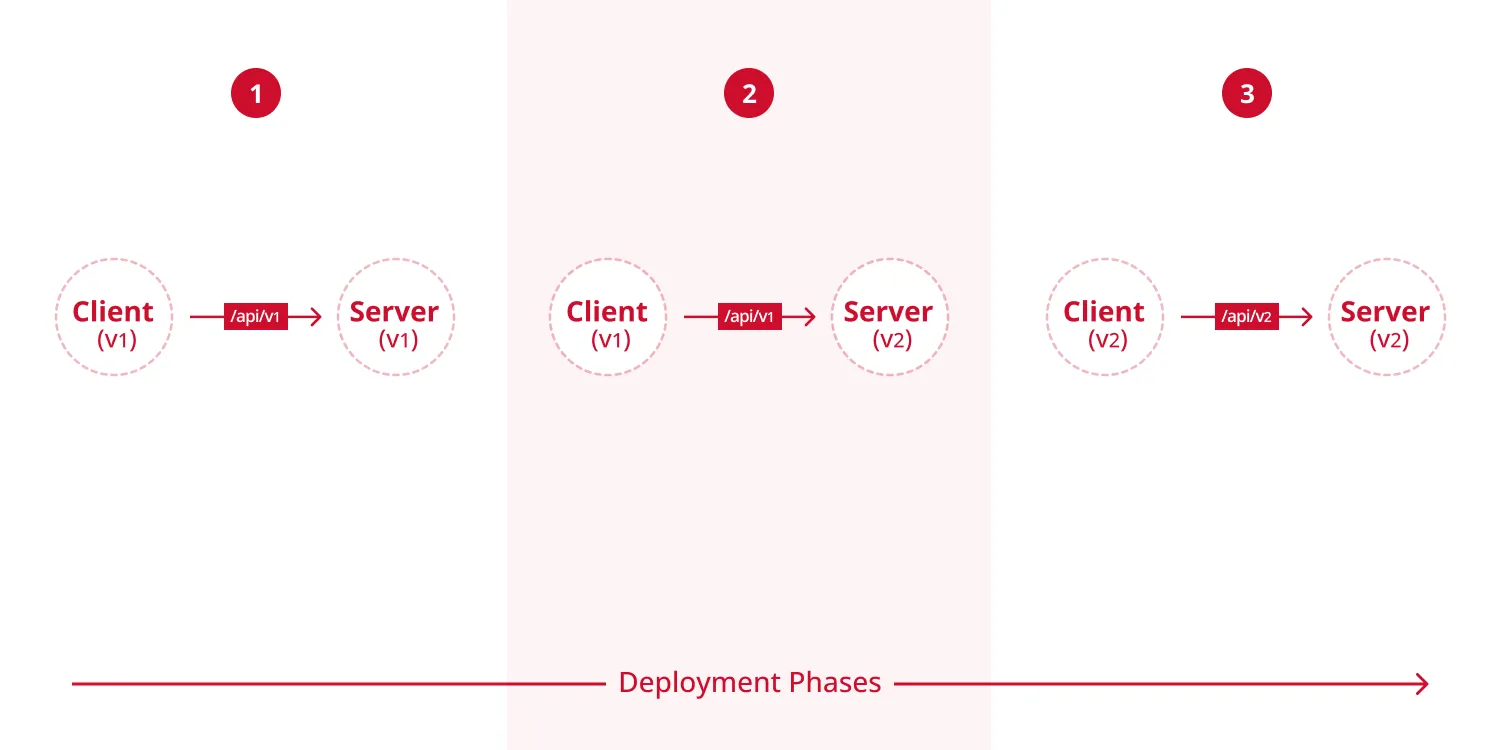

Example II: Consistent Version Environment via API

In this example, we have a client application and a remote server application. The server exposes a distinct API for each released version. When we deploy a new version of the server, it can keep serving requests with the previous versions in a fully backward-compatible manner. This environment guarantees that the client will only interact with the intended version of the server and vice versa.

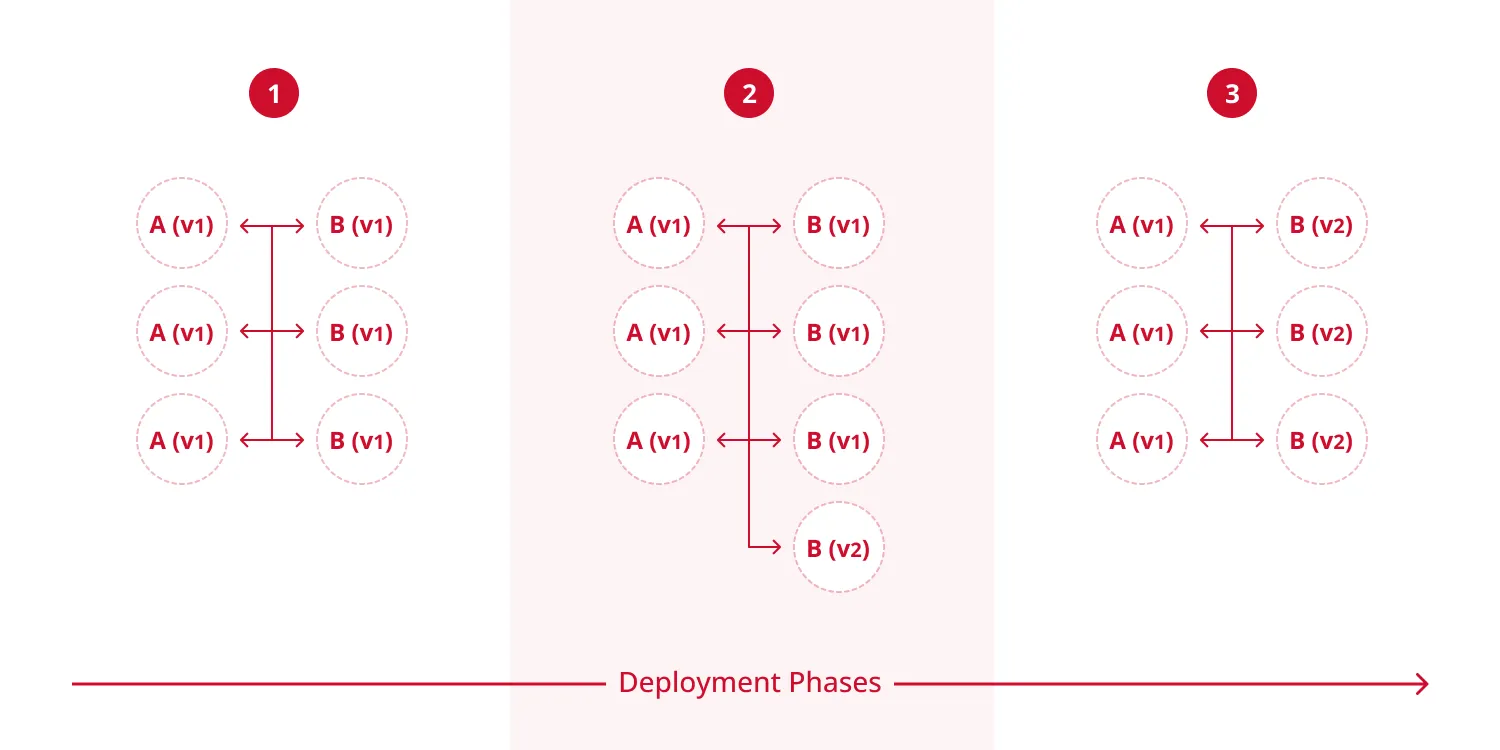

Example III: Inconsistent Version Environment

In this example, we have two different applications, each deployed on dedicated machines. During the deployment of component B , component A will simultaneously interact with two different versions of component B. This environment does not guarantee version consistency. This means backward compatibility of B must be explicitly enforced, otherwise, well…not good things…maybe even bad stuff. 💥 💸 😭

Next Up…

Bear in mind consistent version guarantee. In the upcoming articles, we’re going to discuss the effect of this constraint in each step of our decision-making. I will refer back to the examples whenever needed. Next — version control layout.

What Have I Missed?

Have I missed anything? Please share your thoughts and let me know. ❤️

Special thanks to my superstar colleague Vlad Mayakov for helping in making sense and putting it all together.