TL;DR - This is a quick walkthrough of our experience writing and maintaining integration and end-to-end testing at HUMAN, what we’ve learned, how to apply it, and what are the main alternatives.

Throughout the history of our enterprise product line, we’ve put emphasis on being able to regularly release to production in short intervals. While this allows us to avoid the risk of big releases, it adds a small but continuous risk to the product. To overcome this, we’ve always stressed the importance of integration and end-to-end testing, as well as the importance of developing with a live environment that acts as close to production as possible.

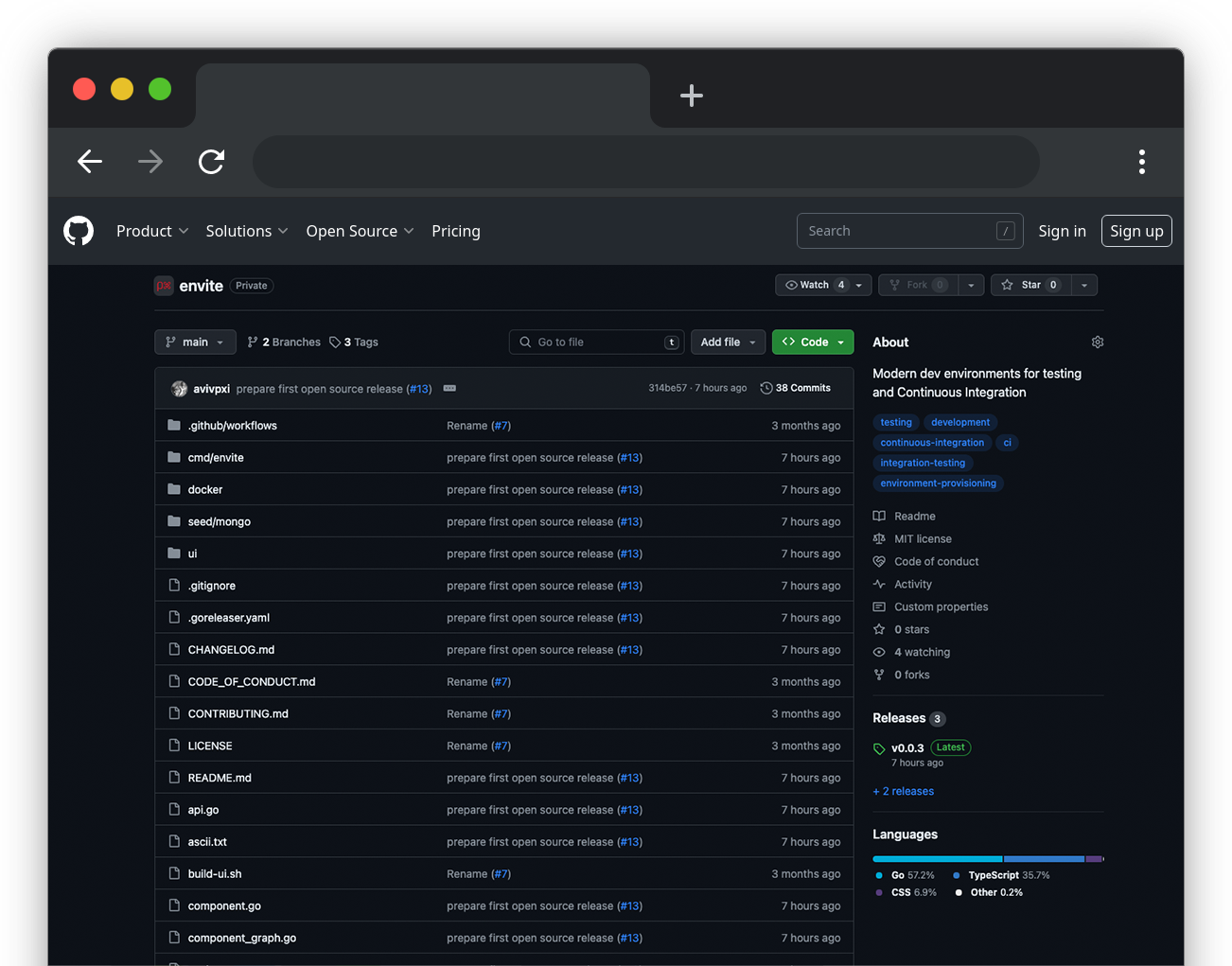

Due to that, we’ve had a lot of expertise around the different use cases of testing environments, their changing needs, and their annoying edge cases. Integration test environments can be very complex to understand, very non-intuitive to manage and maintain, and very hard to execute. Finally, after many years of improvement and iteration, we’ve ended up with a solution that serves as well: ENVITE - a framework to manage development and testing environments.

Why ENVITE?

So why should I Choose ENVITE? Why not stick to what you have today?

For starters, you might want to do that. Let’s see when you actually need ENVITE. Here are the popular alternatives and how they compare with ENVITE.

Kubernetes

This method has a huge advantage: you only have to describe your environment once. This means you maintain only one description of your environments - using Kubernetes manifest files. But more importantly, the way your components are deployed and provisioned in production is identical to the way they are in development in CI.

Let’s talk about some possible downsides:

- Local development is not always intuitive. While actively working on one or more components, there are some issues

to solve:

- If you fully containerize everything, like you normally do in Kubernetes:

- You need to solve how you debug running containers. Attaching a remote debugging session is not always easy.

- How do you rebuild container images each time you perform a code change? This process can take several minutes every time you perform any code change.

- How do you manage and override image tag values in your original manifest files? Does it mean you maintain separate manifest files for production and dev purposes? Do you have to manually override environment variables?

- Can you provide hot reloading or similar tools in environments where this is desired?

- If you choose to avoid developing components in containers, and simply run them outside the cluster:

- How easy it is to configure and run a component outside the cluster?

- Can components running outside the cluster communicate with components running inside it? This needs to be solved specifically for development purposes.

- Can components running inside the cluster communicate with components running outside of it? This requires a different, probably more complex solution.

- If you fully containerize everything, like you normally do in Kubernetes:

- What about non-containerized steps? By that, I’m not referring to actual production components that are not containerized. I’m talking about steps that do not exist in production at all. For instance, creating seed data that must exist in a database for other components to boot successfully. This step usually involves writing some code or using some automation to create initial data. For each such requirement, you can either find a solution that prevents writing custom code or containerizing your code. Either way, you add complexity and time. But more importantly, it misses the original goal of dev and CI being identical to production. These are extra steps that can hide production issues, or create issues that aren’t really there.

- What about an environment that keeps some components outside Kubernetes in production? For instance, some companies do not run their databases inside a Kubernetes cluster. This also means you have to maintain manifest files specifically for dev and CI, and the environments are not identical to production.

Docker Compose

If you’re not using container orchestration tools like Kubernetes in production, but need some integration between several components, this will probably be your first choice.

However, it does have all the possible downsides of Kubernetes mentioned above, on top of some other ones:

- You manage your docker-compose manifest files specifically for dev and CI. This means you have a duplicate to maintain, but also, your dev and CI envs can potentially be different from production.

- Managing dependencies between services is not always easy - if one service needs to be fully operational before another one starts, it can be a bit tricky.

Remote Staging/Dev Environments

Some cases have developers use a remote environment for dev and testing purposes. It can either be achieved using tools such as Kubernetes, or even simply connecting to remote components.

These solutions are a very good fit for use cases that require running a lot of components. I.e., if you need 50 components up and running to run your tests, running it all locally is not feasible. However, they can have downsides or complexities:

- You need internet connectivity. It sounds quite funny because you have a connection everywhere these days, right? But think about the times that your internet goes down, and you can at least keep on debugging your if statement. Now you can’t. Think about all the times that the speed goes down, this directly affects your ability to run and debug your local code.

- What if something breaks? Connecting to remote components every time you want to do any kind of local development simply add issues that are more complex to understand and debug. You might need to debug your debugging sessions.

- Is this environment shared? If so, this is obviously bad. Tests can suddenly stop passing because someone made a change that had unintended consequences.

- If this environment is not shared, how much does it cost to have an entire duplicate of the production stack for each engineer in the organization?

TestContainers

This option is quite close to ENVITE. TestContainers and similar tools allow you to write custom code to describe your environment, so you have full control over what you can do. As with most other options, you must manage your test env separately from production since you don’t use testcontainers in production. This means you have to maintain 2 copies, but also, production env can defer from your test env.

In addition, testcontainers have 2 more downsides:

- You can only write in Java or Go.

- testcontainers bring a LOT of dependencies.

How’s ENVITE Different?

With either option you choose, the main friction you’re about to encounter is debugging and local development. Suppose your environment contains 10 components but you’re currently working on one. You make changes that you want to quickly update, you debug and use breakpoints, you want hot reloading or other similar tools - either way, if you must use containers it’s going to be harder. ENVITE is designed to make it simple.

ENVITE supports a Go SDK that resembles testcontainers and a YAML CLI tool that resembles docker-compose. However, containers are not a requirement. ENVITE is designed to allow components to run inside or outside containers. Furthermore, ENVITE components can be anything, as long as they implement a simple interface. Components like data seed steps do not require containerizing at all. This allows the simple creation of components and ease of debugging and local development. It connects everything fluently and provides the best tooling to manage and monitor the entire environment. You’ll see it in action in a minute.

Does ENVITE Meet My Need?

As with other options, it does mean your ENVITE description of the environment is separate from the definition of production environments. If you want to know what’s the best option for you - If you’re able to run testing and local dev using only production manifest files, and also able to easily debug and update components, and this solution is cost-effective - you might not need ENVITE. If this is not the case, ENVITE is probably worth checking out.

At some point, we plan to add support to read directly from Helm and Kustomize files to allow enjoying the goodies of ENVITE without having to maintain a duplicate of production manifests.

Another limitation of ENVITE (and most other options as well) - since it runs everything locally, there’s a limit on the number of components it can run. If you need 50 components up and running to run your tests, running it all locally might not be feasible.

Note: Another interesting thing worth checking out is Raftt. They run your environments remotely and allow ease of debugging and development experience. If that sounds like what you need, I suggest reading more about what they do.

Within the company, we use ENVITE to define testing environments for each service or group of services. Then, we use it locally to develop and write tests. Then we validate changes by running these tests on CI processes.

Usage

ENVITE offers flexibility in environment management through both a Go SDK and a CLI. Depending on your use case, you can choose the method that best fits your needs.

The Go SDK provides fine-grained control over environment configuration and components. For example, you can create conditions to determine what the environment looks like or create a special connection between assets, particularly in seed data. However, the Go SDK is exclusively applicable within a Go environment and is most suitable for organizations or individuals already using or open to incorporating it into their tech stack. Regardless of the programming languages employed, if you opt to write your tests in Go, the ENVITE Go SDK is likely a more powerful choice.

Otherwise, the CLI is an easy-to-install and intuitive alternative, independent of any tech stack, and resembles docker-compose in its setup and usage. However, it’s more powerful than docker-compose in many use cases as mentioned above.

CLI Usage

- Install ENVITE from our GitHub releases page.

- Create an envite.yml file:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

default_id: "my-test-env"

components:

-

persistence:

type: docker component

image: mongo:7.0.5

name: mongo

ports:

- port: '27017'

waiters:

- string: Waiting for connections

type: string

cache:

type: docker component

image: redis:7.2.4

name: redis

ports:

- port: '6379'

waiters:

- string: Ready to accept connections tcp

type: string

-

seed:

type: mongo seed

uri: mongodb://:27017

data:

- db: data

collection: users

documents:

- first_name: John

last_name: Doe

- Run

enviteand watch the magic.

Voilà! You now have a fully usable dev and testing environment. Note how these are not only docker containers, you can run seed steps or any other implementation of the envite.Component interface. In the demo above, the environment is not only up and running but also seeded with the test data you’ve defined.

The full list of CLI supported components can be found here.

The UI is designed not only to be convenient and intuitive but also to allow running some components outside docker, allowing you to run components in debug mode, use hot reloading, restart them, and integrate local changes quickly.

Note how the components array contains two elements. Each element represents a layer of components that can be started in parallel and have dependencies in the components from the previous layer.

Go SDK Usage

Using the Go SDK allows you to reach the same result, but it can be much more powerful as you can use imperative programming to describe your environment. In addition, you can integrate the components and environments into the logic of your tests.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

package main

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/docker/docker/client"

"github.com/perimeterx/envite"

"github.com/perimeterx/envite/docker"

"github.com/perimeterx/envite/seed/mongo"

)

func runTestEnv() error {

dockerClient, err := client.NewClientWithOpts(client.FromEnv, client.WithAPIVersionNegotiation())

if err != nil {

return err

}

network, err := docker.NewNetwork(dockerClient, "docker-network-or-empty-to-create-one", "my-test-env")

if err != nil {

return err

}

persistence, err := network.NewComponent(docker.Config{

Name: "mongo",

Image: "mongo:7.0.5",

Ports: []docker.Port,

Waiters: []docker.Waiter{docker.WaitForLog("Waiting for connections")},

})

if err != nil {

return err

}

cache, err := network.NewComponent(docker.Config{

Name: "redis",

Image: "redis:7.2.4",

Ports: []docker.Port,

Waiters: []docker.Waiter{docker.WaitForLog("Ready to accept connections tcp")},

})

if err != nil {

return err

}

seed := mongo.NewSeedComponent(mongo.SeedConfig{

URI: fmt.Sprintf("mongodb://%s:27017", persistence.Host()),

})

env, err := envite.NewEnvironment(

"my-test-env",

envite.NewComponentGraph().

AddLayer(map[string]envite.Component{

"persistence": persistence,

"cache": cache,

}).

AddLayer(map[string]envite.Component{

"seed": seed,

}),

)

if err != nil {

return err

}

server := envite.NewServer("4005", env)

return envite.Execute(server, envite.ExecutionModeDaemon)

}

The Result

With either approach, you can execute ENVITE in one of three modes: start, stop, and daemon. The first two allow you to manage the environment where you only need to run it as a whole. Typically, this would be the case for CI or other automated processes. The third, daemon option, is the default mode. It fires a browser-based UI that you’d typically want to use for local work. It enables managing the environment, monitoring, initiating and halting components, conducting detailed inspections, debugging, and providing all essential tools for development and testing. The daemon mode is showcased in the video above.

If you’re further interested in the API and use cases of ENVITE, check out the full README, and Go Docs.