This post covers Go variable behavior, including mutability, function pass types, zero values, and common pitfalls to avoid.

Variable Type Behavior

Mutability

What will the following python code print?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

def func1():

x = 1

func2(x)

print(x)

def func2(x):

x += 1

func1()

Click to reveal answer

The answer is `1`. Integers are immutable in Python, so `x += 1` in `func2` creates a new local variable rather than modifying the original.What will the following python code print?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

def func1():

x = {"key": 1}

func2(x)

print(x["key"])

def func2(x):

x["key"] += 1

func1()

Click to reveal answer

The answer is `2`. Dictionaries are mutable in Python, so the modification in `func2` affects the original dictionary.Primitive Vs. Non-Primitive

If you’ve programmed in either Python, JavaScript, Java, C#, PHP and many more languages, this should feel very intuitive:

- Primitive variables are immutable.

- Non primitive variables are mutable.

Why? Function pass types.

Function Pass Types

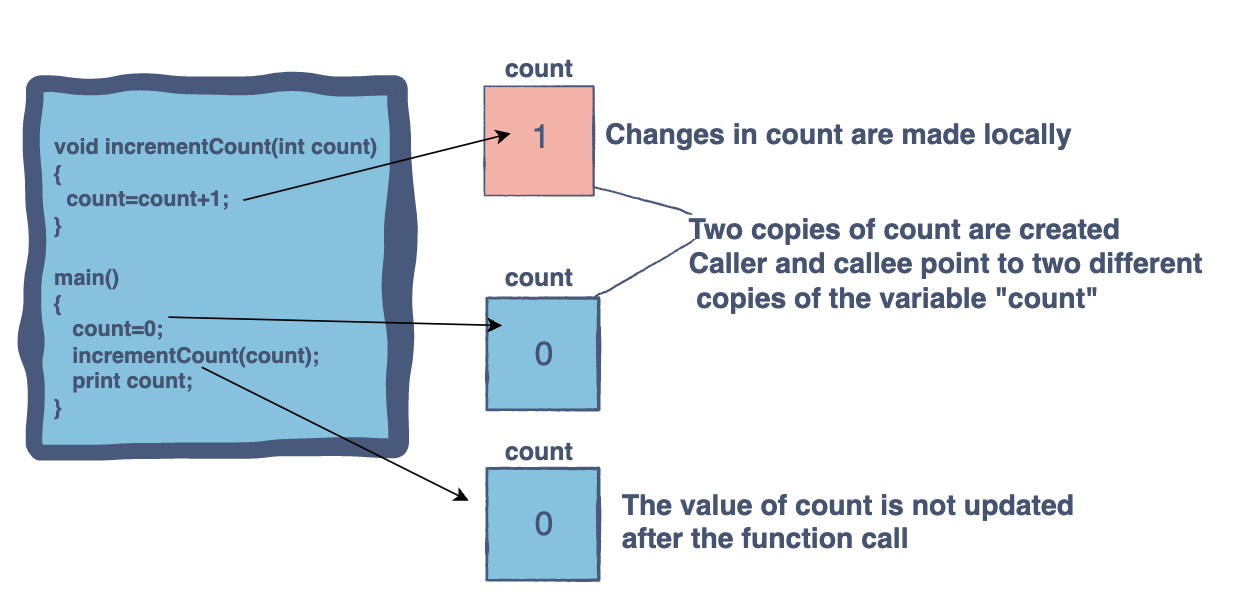

Pass By Value

In pass by value:

- Two copies of

countare created - Caller and callee point to two different copies of the variable

count - Changes in

countare made locally - The value of

countis not updated after the function call

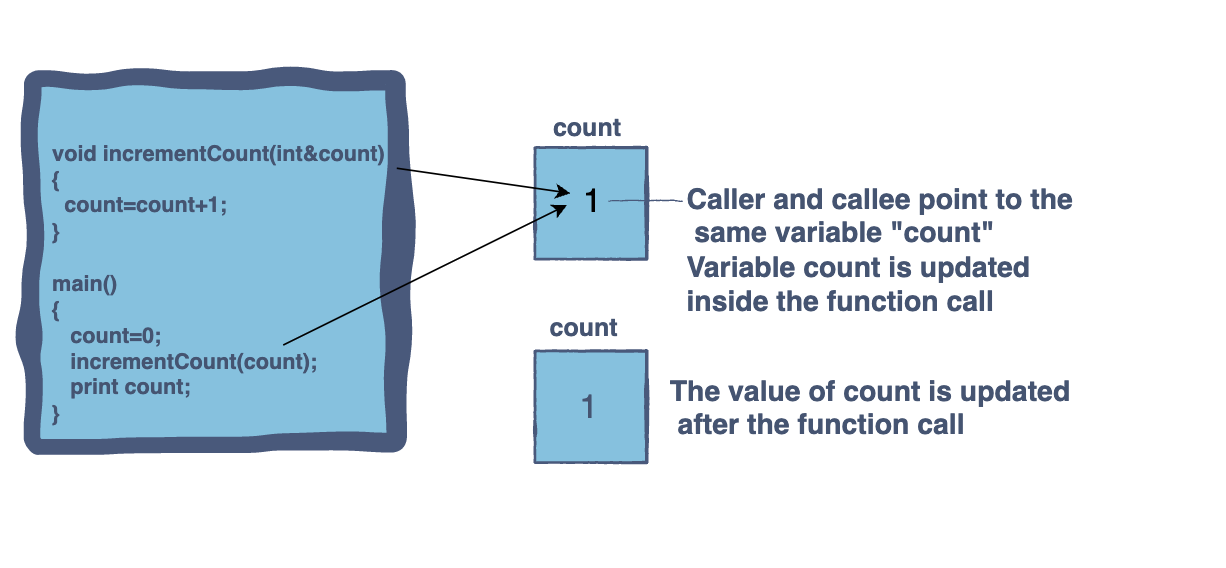

Pass By Reference

In pass by reference:

- Caller and callee point to the same variable

count - Variable

countis updated inside the function call - The value of

countis updated after the function call

Go Function Pass Types

Pass By Value

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

func main() {

i := 1

f(i)

}

func f(i int) {

i++

}

In Go, every variable type can be passed by reference if it’s a pointer.

Pass By Pointer

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

func main() {

i := 1

f(&i)

}

func f(i *int) {

*i++

}

Zero Values

Nullability

Only the following types can be nil:

- pointer types

- map types

- slice types

- function types

- channel types

- interface types

As opposed to other languages: structs cannot be nil unless they are pointers, and “primitives” can be nil if they are pointers. Due to that, Go does not have the notion of primitive variables.

Zero Values

What will be the value of someVariable?

1

2

3

4

func main() {

var someVariable int

fmt.Println(someVariable)

}

Zero value by type:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

| Type | Value |

|--------------------------|-----------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Numeric variables | `0` |

| Strings | `""` |

| Booleans | `false` |

| Structs | instance of the struct with all fields initialized to their own zero values |

| Arrays (but not slices) | all elements inside initialized to their own zero values |

| Everything else | `nil` |

Struct Zero Value

What will be the zero value of the following struct:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

type Parent struct {

a int

b string

c bool

d child

}

type child struct {

a float64

b chan bool

}

func main() {

var someVariable Parent

fmt.Println(someVariable)

}

Click to reveal answer

Output: {0 false {0 <nil>}}

a int→0b string→""(empty string, appears as space in output)c bool→falsed child→{0 <nil>}(float64 is0, chan bool isnil)

Variable Behavior

Behavior of Arrays

Arrays have fixed size:

1

2

3

4

5

func main() {

var x [4]int

x[1] = 1

fmt.Println(x) // [0 1 0 0]

}

Behavior of Slices

Slices have dynamic size but they use a backing array. Slices can be seen as pointers to their backing array.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

func main() {

x := []int{1, 2, 3, 4}

y := x[1:]

fmt.Println(y) // [2 3 4]

mutateSlice(y)

fmt.Println(x) // [1 2 14 4]

}

func mutateSlice(y []int) {

y[1] = 14

}

Slices have len and cap, where:

lenis the length of the slice and the last relevant element in the backing arraycapis the current capacity of the slice and size of the backing array

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

func main() {

result := make([]int, 2, 4)

result[0] = 1

result[1] = 2

fmt.Println(result) // slice is [1 2]

// backing array is [1, 2, 0, 0]

}

What will happen here?

1

2

3

4

5

6

func main() {

result := make([]int, 2, 4)

result[0] = 1

result[1] = 2

fmt.Println(result[2])

}

Click to reveal answer

panic: runtime error: index out of range [2] with length 2 goroutine 1 [running]: main.main() Process finished with the exit code 2Creating a new slice

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

func appendSuffixToSliceElements(slice []string, suffix string) []string {

result := []string{}

for _, element := range slice {

result = append(result, element + suffix)

}

return result

}

Empty slices behave like nil (with one exception, JSON marshalling produce null instead of []), but the performance is better.

This is a bit better, but still has bad performance when the slice grows beyond its capacity, causing repeated reallocations:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

func appendSuffixToSliceElements(slice []string, suffix string) []string {

var result []string

for _, element := range slice {

result = append(result, element + suffix)

}

return result

}

Improve it by creating the backing array with the required capacity when possible:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

func appendSuffixToSliceElements(slice []string, suffix string) []string {

result := make([]string, 0, len(slice))

for _, element := range slice {

result = append(result, element + suffix)

}

return result

}

But note the difference between len and cap.

What happens if you specify len instead of cap?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

func main() {

slice := []int{1, 2, 3}

result := make([]int, len(slice))

for _, i := range slice {

result = append(result, i)

}

fmt.Println(result) // [0 0 0 1 2 3]

}

vs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

func main() {

slice := []int{1, 2, 3}

result := make([]int, 0, len(slice))

for _, i := range slice {

result = append(result, i)

}

fmt.Println(result) // [1 2 3]

}

Behavior of Maps

Maps are always effectively pointers:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

func main() {

x := map[string]interface{}{"a": 1}

fmt.Println(x) // map[a:1]

mutateMap(x)

fmt.Println(x) // map[a:false]

}

func mutateMap(x map[string]interface{}) {

x["a"] = false

}

Pitfalls & Code Smells

Pointer to non-structs

Pointer to non structs can be considered as code smells. Usually, they can be refactored to a function that takes a value and returns a value, instead of a mutating function. (pure functions, no side effects).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

func main() {

x := 3

y := 4

add(&x, y)

fmt.Println(x) // 7

}

func add(x *int, y int) {

*x = *x + y

}

Pure functions are:

- More readable

- Easier to reason about

- Easier to combine

- Easier to test

- Easier to debug

- Easier to parallelize

Better approach:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

func main() {

x := 3

y := 4

x = add(x, y)

fmt.Println(x) // 7

}

func add(x int, y int) int {

return x + y

}

Pointers to interfaces

Pointers to interfaces will not work as you expect:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

type SomeInterface interface {

Foo()

}

func main() {

var x *SomeInterface

x.Foo() // Unresolved reference 'Foo'

}

The nil interface pitfall

What will this function print:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

func main() {

err := validateAge(19)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("you are younger than 18")

} else {

fmt.Println("you are older than 18")

}

}

func validateAge(age int) error {

var err *TooYoungError = nil

if age < 18 {

err = &TooYoungError{}

}

return err

}

type TooYoungError struct {}

func (t *TooYoungError) Error() string { return "too young" }

Output:

1

you are younger than 18

Wait, what? Age 19 should pass validation! This is the bug - the nil interface pitfall in action.

In Go, error is a builtin interface:

1

2

3

type error interface {

Error() string

}

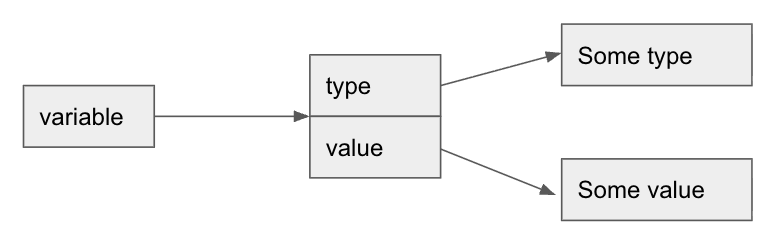

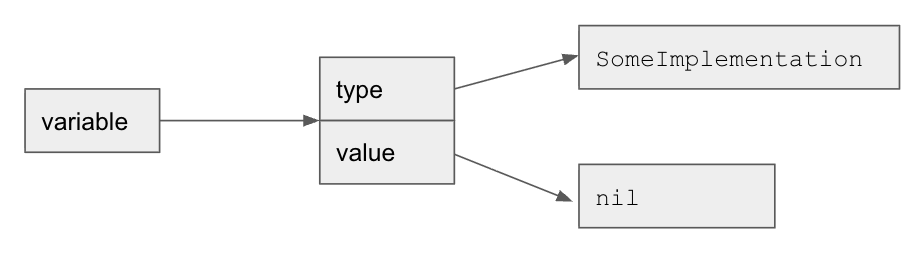

To understand what happens, let’s look at Go’s interface variable memory layout:

An interface variable contains two parts:

type- pointing to the concrete typevalue- pointing to the actual value

Meaning, if we set a concrete type to an interface variable, even if the actual value is nil, it will be a non-nil interface pointer, which points to a nil value.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

func main() {

var x *SomeImplementation = nil

var y SomeInterface = x

fmt.Println(y) // <nil>

fmt.Println(y == nil) // false

}

type SomeInterface interface {

Foo()

}

type SomeImplementation struct {}

func (s *SomeImplementation) Foo() {}

How can we avoid it? Always declare error variables as error.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

func validateAge(age int) error {

var err error

if age < 18 {

err = &TooYoungError{}

}

return err

}

Output:

1

you are older than 18

For loop variable capture

Let’s discuss for loop behavior: what will be the output of the following code? Also, what is the Sleep call for?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

func main() {

x := []int{1, 2, 3, 4}

for _, i := range x {

go func() {

fmt.Println(i)

}()

}

time.Sleep(time.Second)

}

Output:

1

2

3

4

4

4

4

4

How to fix it?

Option 1 - Pass as parameter:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

func main() {

x := []int{1, 2, 3, 4}

for _, i := range x {

go func(i int) {

fmt.Println(i)

}(i)

}

time.Sleep(time.Second)

}

Option 2 - Create a new variable:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

func main() {

x := []int{1, 2, 3, 4}

for _, i := range x {

i := i

go func() {

fmt.Println(i)

}()

}

time.Sleep(time.Second)

}

As of Go 1.22, this is no longer an issue. However, you’ll still see many of these in many Go codebases.